#Column

Seeing the Forest for the Trees

The Future Library: Bearing our stories into 2114

“I’m thinking of doing a sort of ‘textual pilgrimage’ to the Library of the Future over Easter break,” is what I messaged my editor back in March. “I’m getting a bit sentimental,” I explained. I’ll be graduating soon. I’m at stage four of thesis writing, which means it’s metastasized to the rest of my thought processes. I was having a hard time seeing the forest for the trees and needed a bit of perspective. “Great!” Arina wrote back, “That is, what do you mean by textual pilgrimage?”

Writing Blindly into the Future

Even before I arrived in Norway, I knew I wanted to visit the Future Library. There was something about its relationship to the future, to the past, that struck a chord in me.

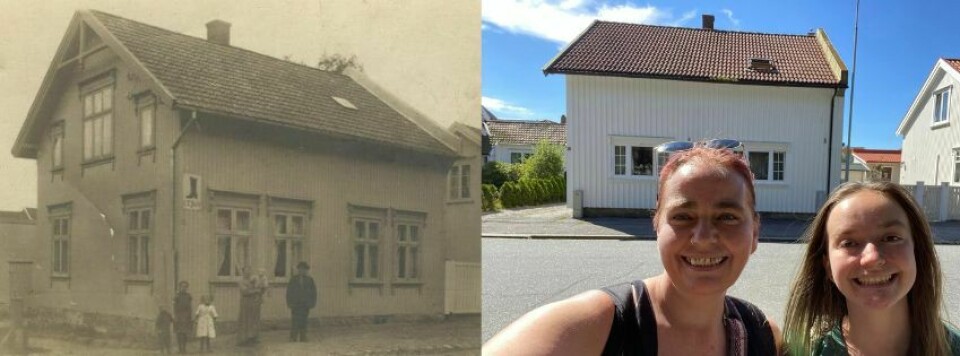

When my grandmother died in 1997, she left a handwritten manuscript under her bed. My mother and I found it as we were cleaning out her things: a thick, yellow spiral-bound notebook detailing my grandmother’s childhood in Larvik, her years as a young mother in Tønsberg during WWII, and her move to Amerika with my mom and grandfather in the 1950s. Born in 1903, just a few years before Norway achieved independence, my grandmother was the last surviving sibling of eleven. Her mother was a cook from Tjølling. Her father was from Svarteborg. He lost his parents in a smallpox epidemic when he was fourteen and was working as a traveling shoemaker when he met my great-grandmother, who happened to be cooking in the household of a wealthy family who needed shoes.

With a sixth grade education and swoopy handwriting that had received top scores at school, my grandmother wrote blindly into a future she would never meet. She would never know that I would keep the language she taught me, that I would one day name my daughter after her (and also give her my great-grandmother’s middle name), that I would miscarry twins just as she had in 1931, or that I’d move back to Norway and find work as a cook while completing my second master’s degree.

In a sense, my grandmother has written two books: one about the past, which lies in that spiral bound notebook, and one about the future, which lives on in my own embodied experience and the stories I’ve taken with me. When I’m at work here in Oslo, quartering potatoes and chucking them into boiling water, I daydream about my great-grandmother from Tjølling, about my great-uncles who found work at fourteen peeling potatoes on ships, the smoothness of my own grandmother’s hands as she taught me how to use a knife. The stories never told me where to go, but they gave me a sense of direction when I got there.

The Future Library Concept

NORLA video on Future Library

It’s the interplay between the past and the future that has so fascinated me about the Future Library, a concept devised by Katie Paterson, who planted 1,000 trees in Nordmarka in 2014 as part of this project. Every year since then, an accomplished author has contributed a manuscript to a collection housed in The Silent Room on the fifth floor at Deichman Bjørvika. These manuscripts will remain sealed until 2114, at which point they will be printed on paper made from these hundred-year trees and made available to the public. The project isn’t just about the stories. It’s also about their embodiment, the trees that will bear them. It’s also about time.

I did the math. Neither I nor my daughter will be around when these manuscripts come to light. A grandchild just might be alive, but a great-great grandchild would be the one most likely to read the texts coming out of this project. It kind of blows my mind. Assuming I even have a great-grandchild, who will this person be? What parts of my own story will have stayed with them? What other stories will be there?

I look in the mirror. It’s not my double chin that I see, but my great-grandmother’s, and before her, it belonged to someone else. Like her, I wear black all the time. It’s practical. Assuming I survive the other things, I’ll probably die of a stroke, the way she did, the way I found my mother on the floor, dead of the same back in 2018. Sometimes when my eyes get tired from reading, I will feel my eyelid begin to twitch and think, just for a moment, “well, here it comes.” But just as the sun casts different shadows on the floor as it moves about its day, my reflection shifts to different gradients of the past, uncovering the exact blue of my father’s eyes or my late brother’s crooked smile. This will happen to someone in the future someday, too, but then I’ll be the ghost surfacing beneath their skin. It’s so weird.

That’s what I like about Katie Peterson’s art. It’s so weird because it turns the universe inside out, but only when you stop to think about it. Previous artwork includes a map of all the dead stars in the universe, a live phone-line to a distant glacier, an archive of darkness, and a replica of a meteorite returned to space.

It’s this sort of existential fascination, too, that keeps me glued to my master’s thesis, which I am 73 pages deep into writing. Using nexus analysis as a framework for organizing the data, it tips an ocean of public discourses, lived experiences, geographies, and interactional dynamics into a simple social action and attempts to preserve and explain a few thin slices of time even as time itself is changing everything. I asked one of my advisors if I could write an epic poem about it instead, and she said no. Or rather, she said it wouldn’t be likely to guarantee my degree.

The Future Library has a board of trustees charged with selecting and inviting authors to contribute, in any language they choose. Authors are selected, in part, on the basis of their ability to “capture the imagination of this and future generations.” I admit to wishing this outcome for my master’s thesis, too. I hope the people reading it will recognize something essential about themselves, about society, about the way we tunnel through it. I would also like the degree, though in the end, it’s just a piece of paper. Or…?

The Silent Room

“Take care of your mother,” my grandmother had said to me while dying. My mother, with her nose in a book every time I turned around. She loved art and languages, and had wanted to be either a translator for the UN or a librarian when she was younger, but grew a taste for adventure and became a travel agent instead. She wasn’t like the other mothers I knew. She painted murals on the walls and took us backpacking all over the world. Just hours after her mastectomy, she insisted on going to the circus to see my daughter rehearse, and with her chemotherapy done, looked forward to taking a trip to Pakistan one day to visit the exchange student who had lived with us for a year and become a second daughter.

My mom died in 2018, just a few years before the pandemic hit. I had made her write her own life story down, too, and brought both manuscripts with me to Norway when I moved here in 2022. She died not knowing that my daughter would end up studying circus, first in Portugal and later in the Netherlands. She died before the confusion of the pandemic, before George Floyd was killed just down the street, before my eldest brother was found dead in his apartment. I don’t know how many times I’ve wanted to call her to tell her these things, to let her know that my partner and I went different directions, that I’m in Oslo studying multilingualism, that I rented a table at an artist’s market here and sold two paintings.

The truth is that I wouldn’t have come to Norway if my mother had still been alive. I’d be back in Minneapolis, taking care of her. Sometimes a forest is cleared so that something new can grow, and this is reflected in the design of The Silent Room at Deichman Bjørvika, which was constructed from trees cleared from Nordmarka prior to that first planting in 2014. Like memories, the old trees were cut into 16,000 fragments and layered into a hundred years worth of time. Each layer contains a drawer into which one manuscript will be encased. So far, manuscripts from Margaret Atwood, Tsitsi Dangarembga, David Mitchell, Judith Schalansky, Elif Shafak, Sjón, Han Kang, Karl Ove Knausgård, and Ocean Vuong have nested here.

I’ve only read some of these authors. Karl Ove Knausgård did a reading once at the University of Minnesota, where I did my undergrad. I remember him in dark clothes, leaned up against the side of the building, smoking a cigarette before he went in. I found the excessive detail of his writings maddening at first, then addictive. Crawling into someone else’s story is a peculiar kind of intimacy. It’s something about the details, the things they notice that you don’t.

The Silent Room is small, so you can’t have too many people in there at one time. It feels a bit like a tomb and, since you have to take your shoes off to go in, smells unmistakably of feet. But it’s also cozy and womb-like, and makes sense when you consider the odyssey by escalator through Deichman Bjørvika to the fifth floor. Entering at ground level, you can’t help but see the sprawl of neon roots holding up a ceiling made of honeycomb. Weaving through a constant stream of patrons who pause abruptly to greet a friend or browse a shelf, there’s an unshakeable sense of being small, like an ant, in a universe of activity. You have to look for the escalators, follow the chemical trace of movement. Somewhere around the third floor, the cosmos above begins to open up.You see the sky above, the layering of life, the immensity of the place in which you are standing. By the fifth floor, you’re following the curve of things, looking for a place to nest. This is when you see it. You feel like you have to go through that portal.

The Future Library Forest

I started writing when I was very young, phonetically sounding out the words I didn’t know how to spell. A lot of my early stories were escapist, some about a little girl joining the circus, and it seems absurd to say it now, but it’s almost like I was writing my own daughter into existence, long before her time. I was never an athlete myself, more of a floating head, but have always been compelled by the thought of a world where anything can happen. I rediscovered some of these old stories as I was packing up for my move to Norway, and wondered at all the molecular decisions that had led to my daughter embodying those early stories. Somewhere along the line, the stories had become hers, and she had cultivated them beyond even what I could have envisioned. Who was it that planted this story and when was it that it began to take root?

Determined to personally visit the site of the forest nursing the trees that would become the paper on which the Future Library manuscripts would be printed, I planned an excursion over Easter weekend with a friend who’s fond of throwing my own words back in my face. He chuckles every time he says it, “We shall see what the future brings.” He thinks it’s funny that I have no idea what I’ll be doing after finishing up my master’s thesis. But me, I’m just trying to get through the now for now. I’ve got to finish this thing, and do justice to what I’m writing about. I need to be able to shape where it’s going.

Neither my friend nor I really know how to ski, but unlike trees, we’ve got feet. So, we packed a picnic, pulled up the GPS coordinates on Google Maps (59°59'10.8"N 10°41'48.7"E) and took the #1 metro til Frognerseteren for the journey. And, yes, there’s something about the Easter symbolism of “rising again” that struck me as weirdly appropriate timing-wise. 2114 is when it will happen with these manuscripts. In agreement with the trustees of the Future Library, the city of Oslo has agreed to protect this forest for a hundred years.

There was a lot more snow than we expected, so we took the challenges as they came, nudging our way down slippery slopes, chipping our toes and heels in to gain traction in the crust. Skiers, leggy and elegant, would glide by like gazelles wrapped in thermal suits. We stopped one woman criss-crossing uphill to ask if she had passed the Future Library on her way. She hadn’t even heard of it, but was tickled to find out I was from the US. “Your Norwegian is so good!” She had married a Texan and they had brought their niece out skiing for the day. “Hey,” she shouted uphill, “She’s from Amerika, too!” and the niece sent an underhand wave back from waist level, doing her best to stay upright. “I’m embarrassed,” said the woman with an easygoing grin, “that a couple of foreigners know something about this place that I don’t.”

My master’s thesis in multilingualism is about language and migration. For the past five months, basically everything I see and hear points back to these coordinates. That’s how deep in I am. I’ve been interviewing Norwegians with refugee backgrounds about their experiences contributing to society through volunteerism, particularly those experiences relating to inclusion, language learning, and being the driver of their own choices. In public discourse, refugees are sometimes portrayed as uprooted, rootless, transplanted and displaced on foreign soil. The far right talks about refugees as a sort of invasive species, the far left about biodiversity. It’s all a metaphor, right? But metaphors are important, shaping the way we see the world around us and the action we take in it. I’m interested in understanding what this forest can tell us about the future, and how it can help us to make sense of a world where climate change is setting the stage for conditions of increasing geopolitical instability.

My phone told me that we were minutes away from the Future Library forest. I was desperate to “use the facilities,” but every time I stepped off the path, my leg was plunged knee-deep into snow and my friend had to pull me out again. Eventually, I found a big tree with sprawling roots and used these to stabilize myself while my friend turned his back and scouted out the pathway ahead. When I finally caught up, he was already there, scanning a QR code posted to the side of a tree.

To be honest, at first glance it was underwhelming. In this forest of towering creatures, these Future Library trees were gaunt little saplings nearly covered by snow. I tried to imagine them ninety years from now, to envision these fragile plants bearing our culture into the future on their backs. But it was hard, and at some point I felt like I needed to stop forcing it. What would happen would come. The potential was already there. We’ll see what the future brings. But it had been a nice afternoon, and I appreciated my friend all the more for his willingness to go along with my mad adventure. It’s not easy, you know, to find people like that.

We found a road on the way back and guessed that it would lead us where we needed to go. The walking was easier. We made better time. We didn’t have to struggle so much with every footstep. A second look at my map, however, showed that we were off course. If we wanted to get back to the metro-station, we’d need to cut through the woods. My friend found a tiny footpath heading the right direction, so we hoped for the best and made our way uphill, stopping to eat a slice of bread with cheese when we felt our energy beginning to dwindle.

The last section of path led up what seemed like a 90 degree slope caked with crumbling snow. At least one person had made it through before. We could follow their footsteps, but each step was precarious and there was nothing to hold onto. If one of us fell or slid, we were likely to cascade quite a ways down or be buried in snow. The only other option was to turn back, and so we forged ahead. He made his way up using all four limbs for stabilization. I dug my toes in hard and tested each step, taking his hand those final steps to the top. And we made it.

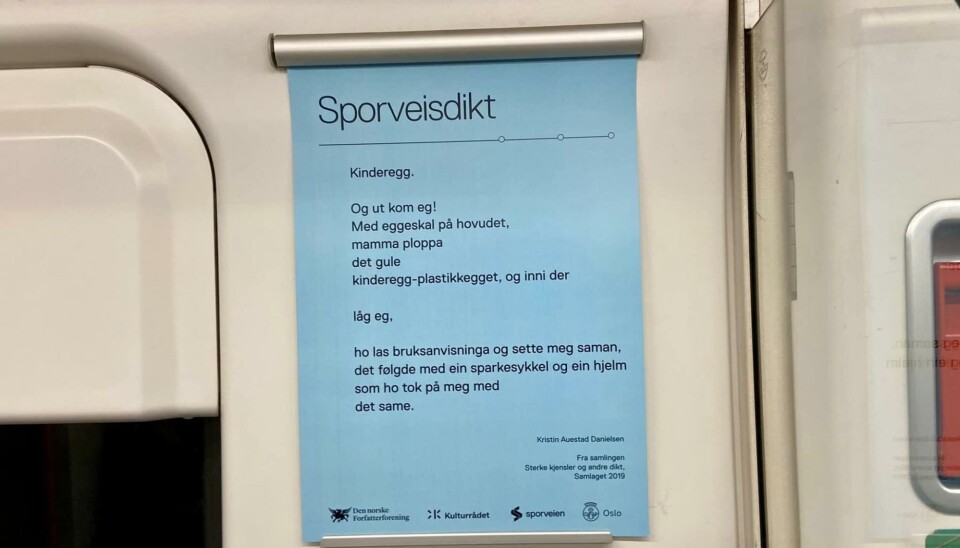

The rest of the way felt like walking home from a long day at a festival. You’ve seen what you wanted to see, had a good time, and now wish someone would just pick you up and carry you the rest of the way. I was tired. On the train again, we rewarded ourselves with an orange and some subway poetry. I think it’s really cool that you can take the subway to the forest, and read poems along the way.

Soft Power

During those last years, when my grandmother was sick, we spent a lot of time together. I spread all the old pictures out on the floor and together, we sorted them into photo albums while she told me stories about all the people in them. Those photos are now crammed into a storage locker in Minneapolis, along with the urns containing my grandmother and mother’s ashes. I sold, gave away, or threw out almost everything else that I owned when I moved here, figuring that the act of returning to “the homeland” would make me a sort of historical vessel in my own right. I had the stories in me. That’s soft power, when you think about it.

During a class I attended before break (part of NorInt 0500, Norwegian life and society), lecturer Erik Juriks talked about literature as a Norwegian soft power, much like that of Hallyu (the Korean Wave) and Japanese Anime and Manga. Since 2004, for instance, NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad) has provided funding to translate approximately 8,000 books from Norwegian into 73 different languages. Although only about 5 million people speak Norwegian, it happens to be one of the top fifteen translated languages in the world. Nordic Noir, Ibsen, and most recently, Jon Fosse, who received the 2023 Nobel Prize in literature, are some examples.

Soft power is the art of influence, seducing others into wanting what you want, shaping their perceptions without twisting any arms. The Future Library is in essence working this soft power into the future, spreading its roots across time. Three, four, five generations from now, people will be reading these stories and feel moved by them, much as I’ve been moved by the stories of my predecessors. Or, for that matter, by the stories my research participants have been sharing with me about their experiences.

These days, writing my thesis, I’ve been walking around with their words in my head. I met with another of my advisors this morning and she commented that I had formatted my interview excerpts like poetry. It was nice, she thought, but she wanted me to work on my analytic structure. I have to post more signs to show the way, and be intentional about my mapping. “First, I’m going to do this, then I’ll do that… make sure you’re always explaining why you’re making these decisions, and why you’re presenting the data in this order.”

I’m having difficulty grasping the edges of things, locating where one thing ends and another begins. It’s all illusory, in a way. Everything goes in circles, like rings marking time in the fibers of a tree. I hand in my thesis on May 15. Eleven days later, on May 26, there will be another manuscript handover in the forest, this time from author Valeria Luiselli. Maybe, if I’m still around, I will be there.