#Culture

Oslo Street Art Scene

What street art can tell you about a city

Sometimes it’s a hastily scrawled picture of a penis on the side of a building or a political sticker on a light pole. Sometimes it’s a mural reflecting the heritage of the area, a tree that’s been yarn-bombed, or an image projected on an exterior wall.

Broadly defined as “public art,” street art (or urban art) is all about taking visual media out of more elite gallery and museum spaces and placing them in a public context. It’s art for the people, art by the people, art meant to create dialogue and reflection for passersby. I like to think of it as the ongoing conversation Oslo is having with itself. When I walk around town, I feel like I’m eavesdropping – and sometimes the conversations are unsettling.

If streets could talk…

Street art as public conversation

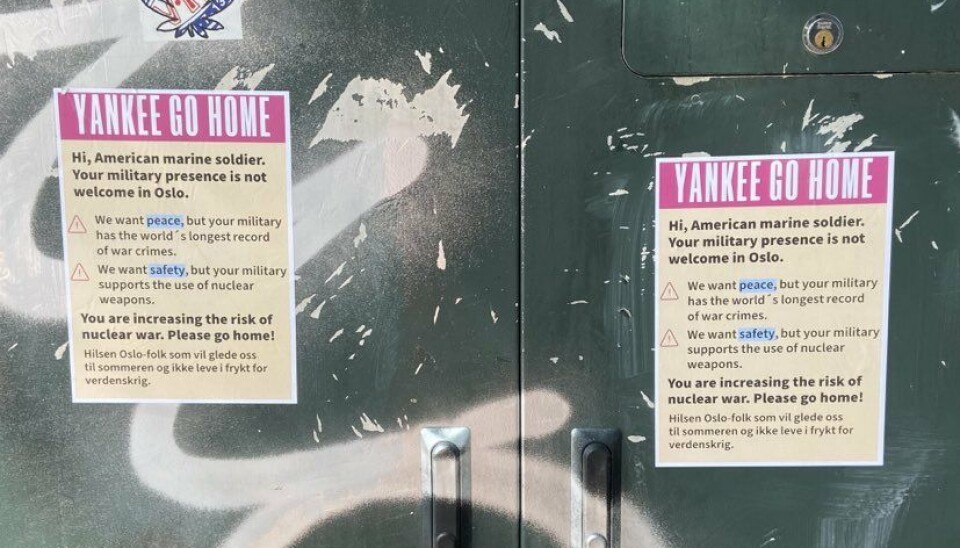

Take, for instance, the “Yankee Go Home'' posters that were pasted up around Oslo last May. As an American, these caught my attention for their use of a phrase that dates back to the American Civil War and has been used in a variety of international contexts to indicate dissatisfaction with American presence on foreign soil. The text of the poster began, “Hi, American marine soldier. Your military presence is not welcome here in Oslo...” and went on to explain how the visit of the warship USS Gerald R. Ford was creating unease and provoking a nuclear threat. Activist and poster-creator Selma Flo-Munch later told NRK that, “There was a man who pushed me and refused to let me put up the posters. He shouted that I was nasty and disgusting before physically attacking me. It got so bad that a passerby had to stop him.”

Street art can pose both questions and responses. During the recent elections in Norway, a street artist joined the debate surrounding “Solbrillegate,” the scandal involving Red Party leader Bjørnar Moxnes, who was caught not paying for a pair of Hugo Boss sunglasses on surveillance video. Töddel‘s painting depicted Moxnes with his pants down, angel wings, and text (in French) that read, “Death to the King,” a commentary on the eagerness of the press to cover the downfall of Moxnes as a political figure. “He's the good boy who's always on the side of the weak, always first out with his pointer finger if others do something wrong, and then he's caught for something like that. The haters love that," Töddel said to VG at the time.

“Is it over for Moxnes?” the painting appeared to be asking. A response came in less than 24 hours. The work, which appeared on a prominent street corner in Bergen, was stolen and replaced by an error message reporting, “No meaning of life,” according to VG. Below was a bulleted list suggesting,“Try: Changing your values, workplace, or partner; Turning off TV and social media.”

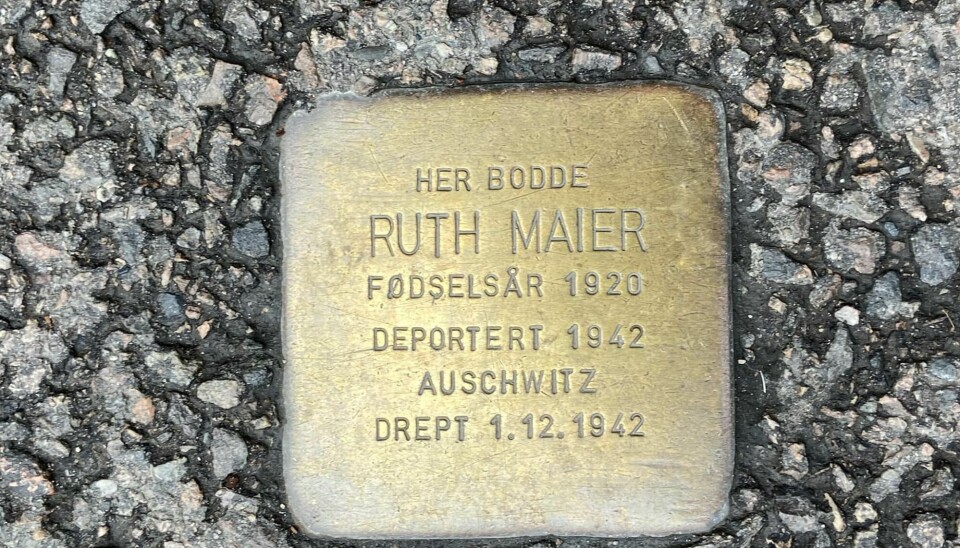

Street art can also serve as a voice of conscience and historical memory, as with the brass plaques, or snublesteiner, that are embedded in Oslo sidewalks outside of the homes and workplaces of Jewish people who were deported to concentration camps during WWII. Each plaque gives the name and birthdate of the person who was deported, as well as their dates of deportation and death. You can look names and places up on Snublestein.no to see photographs and learn more about the lives of those who were killed. According to the website, the project (in 30 European countries) “aims to remind us that the Holocaust happened here as well, and not just somewhere far away.”

Street art as community

Street art can convey rich meanings about local communities, reflecting the presence of many different linguistic groups in the area. I reached out to Haley de Korne, an applied linguist and professor at the Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan, to learn more about the study of language and cultural meanings in public spaces, usually called linguistic landscapes. Haley says, “Originally the field of linguistic landscape studies looked at written languages in public space, such as the use of bilingual signage in streets or the languages on display in a classroom. Now the field has evolved to also consider the semiotic landscape more broadly, including images and symbols that carry social meaning, and can help to make certain people feel included or excluded in different social spaces.”

Haley elaborates, “Language is a multimodal phenomenon (both audio and visual) that is an essential part of how we understand the world and each other. By examining the use of language in public space, we gain insight into language hierarchies (e.g. which languages have more social status or take up more space than others) and whether language laws and rights are being respected. We can put this insight to use in efforts to create public spaces that are inclusive of diverse, multilingual groups.”

“There are multiple social actors who create the linguistic or semiotic landscape in public spaces,” says Haley, “Government officials who decide which language(s) to put on signs play an important role, but many other people, such as street artists and graffiti taggers also leave their mark. Street art can convey important messages about a space, who inhabits it, and who can belong there. Artists don't need words to convey these messages; the meaningful combination of symbols, images and colors can be an effective form of communication, and street art is now considered an important part of the linguistic or semiotic landscape.”

From politics to placemaking

Oslo’s former policy of zero tolerance

If you are wondering about the mixed reactions to street art that you might encounter in Norway, there is a historical context for this ambivalence, according to Emma Arnold, author of “Aesthetics of zero tolerance” (2019). Graffiti, both painting and tagging, came to Oslo with the globalization of hip-hop culture in the 1980s. In the early 90s, the train route between Oslo and Lillehammer was particularly ripe with graffiti. At the time, graffiti and tagging was associated with criminality, which represented a public image problem as the country headed into the 1994 Olympics in Lillehammer.

The years that followed saw an intense shift in public perception of graffiti and tagging in particular, with the Taggerhue Campaign spearheaded by Rune Gerhardsen (Chair of City Council, Oslo 1992-1997). The campaign, which appeared in print, on public transportation and in film trailers, pictured a young male tagger with an empty space in his head that rattled when shaken, conveying a senselessness to the act. Fake fines were sent to the homes of eighth grade students as a way to both scare and school parents on the financial repercussions of tagging. Arnold writes, “The impact of such campaigns on the public imagination should not be underestimated,” suggesting that they propagate the idea of a vandal as young and male, and graffiti as the gateway to other crimes.

In 2000, the city of Oslo cracked down with a zero tolerance policy relating to graffiti, following the “broken windows” theory that aligns graffiti with anti-social behavior leading to more serious crime. According to Arnold, the broken windows theory has since “been highly criticised, in large part due to its lack of robust empirical foundation, particularly with regards to graffiti.” (On a side note, I asked a co-worker who grew up in Oslo what she thought about this policy. She chuckled and said, “The people I knew back then who were into graffiti? They ended up becoming artists as adults”).

As acceptance of street art has grown worldwide, attitudes in Oslo have also taken a turn towards understanding graffiti as an expressive art. In 2016, the City of Oslo issued a Street Art Action Plan which aims to leverage street art to promote tourism and economic growth, positioning Oslo as a street art capital. Even so, penalties for graffiti and tagging remain stringent, with hefty fines and potential imprisonment (see penal code sections below).

Legal-walls.net tracks walls that are safe to spray, identifying approximately 20 locations in Norway, and two in Oslo where graffiti artists can go to practice their craft. Street Art Oslo and Urbant Verksted also offer graffiti workshops for those interested in learning more.

Changing attitudes toward street art in Oslo

When Street Art Oslo put out a call for volunteers last summer to work their third annual Street Art Festival in June, I was excited to sign up. Their mission is “to provide a bridge between street art and graffiti subcultures and the wider public. In doing so we aim to highlight non-institutional approaches to kunst i mellomrom (art in in-between spaces) and to inspire a shared sense of ownership over the visual realm in public space.” According to Hanne Uglestad, the managing director of Street Art Oslo, the organization is “dedicated to improving conditions for the production and dissemination of street art and graffiti by contextualising them within the wider fields of visual art, aesthetics, architecture, urbanism, sociology, anthropology, citizenship and education.”

While participating artists were creating a variety of works around Grünerløkka as part of the festival, I spent two days assisting teaching artists as they led workshops on both spray can graffiti (on cellophane wrap at Sofienbergparken) and nature-based stencil graffiti (Klimahuset, Tøyen Botanical Gardens). I learned some cool techniques and got to chat about art and engagement with young people and adults from many backgrounds. One participant wanted to learn more about translating scientific ideas into visual schematics. Another wanted to try writing in Mandarin, his mother tongue. Parents called out to their children in a number of languages, hoping to catch their child’s attention long enough to snap a picture of them with their creation. This same multifaceted enthusiasm resurfaced when I volunteered again during Grønlandfest.

“Perceptions have definitely changed,” says Hanne, “but there is still a lot of social stigma around graffiti in particular. The city’s hardline zero-tolerance approach was very successful in the sense that many people still find it difficult to judge the aesthetics and quality of graffiti and tagging in particular on its own terms, without getting caught up in the legal-illegal dichotomy. I prefer using the term unsanctioned art about the artworks that have been made without formal permission. This also opens up for reflecting about who has the power to grant these permissions, and who has access to even be heard asking.”

Hanne continues, “But generally people are much more open-minded now, and they want to understand and know more about it. For instance, we do senior-tours regularly, and these are among the best attended tours we do. This generation were young adults during the zero-tolerance years, and are interested to learn about the local history, the politics around it, and also they are very keen to hear about the artists and what they are making. Generally I would say that our audience at least are more open to learn about what they don’t understand, instead of simply just rejecting it or being provoked by it, which I think is a very important quality these days. I also think that street art can open up these topics for people, which is why it’s so important.”

Placemaking

Since moving to Norway last year, I’ve lived in student housing in both Grünerløkka and Tøyen, Oslo neighborhoods characterized by a high density of murals and graffiti. Walking tours in these areas abound. I’ve joined some and eavesdropped on others from the comfort of my own apartment, delighted to be both a visitor and a part of the scenery. VisitOslo, VisitNorway, Fodors, Trip Advisor, Culture Trip and other tourist-oriented sites all feature pages dedicated to the street art here; it’s clear from all this activity that street art brings tourism dollars into the area.

I’m also mindful of the conversations around gentrification that are taking place around me. As rents go up, long-term residents of these increasingly trendy neighborhoods are priced out, pushed further out of the city into more affordable housing (and longer commutes). Some of the street art you can find today in Tøyen came about as part of the Tøyenløftet (Tøyen promise), created to lift up the “troubled” neighborhood when the Munch Museum was relocated to Bjørvika ten years ago. Oslo Mayor Marianne Borgen recently visited Tøyen to talk about some of the successes and challenges of this promise, addressed in a new book by Hanne Mauno, Mother Oslo. Some claim that it wasn’t so much that the area that was lifted up, but that its poorest residents were forced out.

“I think for belonging, making art where people are, is incredibly important. It is also important to support the local scene, and nourish the community,” says Hanne Uglestad, who is busy preparing for Mellomfestivalen (November 3-5), a neighborhood art-project. “We are working with local schools, senior centers, and the church, to empower the local community and neighbors of Sofienberg church and park to activate and change their surroundings through art and creative interventions.”

“We want Oslo’s own street art and graffiti, and not just to invite the ‘big’ names. It’s good to have a mix of both. Street art can be used as a tool for gentrification, and we try to avoid that as much as we can, in selecting the projects and artists that we work with.” Hanne clarifies, “This is also why we are vocal about the importance of unsanctioned art.“ Street Art Oslo has recently opened a second office at Gamle Munch, and is working on developing a program with exhibitions and conferences related to the field.

Cool street art areas in Oslo to explore

Exploring street art is all about the spirit of discovery, so I won’t hand you a map of top-ten works to visit. Instead, I’ll point you to areas where you can spend a good amount of time looking while you wander.

Grünerløkka

A rich vein of street art can be found along Akerselva, around Ingens Gate and Hausmania, and from Thorvald Meyers gate spreading into the side streets of Rødeløkka. My very favorite memory of living in Grünerløkka was smelling fresh paint just as I turned a corner, only to find about half a dozen artists working on a wall late one night. Magical!

Økern Utegalleri at Økernsenteret

Built in 1969, Økernsenteret was once one of Norway’s tallest and most modern shopping centers. It’s been sitting empty since 2015 and is currently awaiting redevelopment. Street Art Oslo teamed up with local Økern-company Resirquel and the graffiti community in Oslo to create this stunning gallery space along the sprawling lower level. A zine about this project is forthcoming.

Tøyen

Tøyen features some lovely large scale murals. Try walking from Tøyen Torg towards Grønland and you’ll find a bunch of them, as well as some cool graffiti work. My favorite is “The Treasure Hunter” by a Chilean artist named INTI who describes himself as a “frustrated astronaut” who paints “because [he] cannot go to the moon.”