Confessions of a working-class girl in academia

Academia isn’t for everyone. But Norway’s social democracy pushes people into universities with promises of equality.

It was while sitting in sociology class, first row, that my world began to unravel. I was listening to a lecture about inequality, and suddenly I understood. The teacher was talking about me. I was one of the students who, according to the statistics, had a much lower chance of completing my higher education, all because my parents never got one.

According to Statistics Norway (SSB), only 40 percent of students with parents who only have primary school education will complete their higher education within 10 years of starting. Meanwhile the corresponding number for students with parents who completed higher degrees is 73 percent.

That bleak statistic sank in my stomach with a feeling of existential angst. I ran out of class and cried in the bathroom. Who did I think I was? I was filled with overwhelming shame. I thought I could fool myself, really believing I could be something (though I couldn’t comprehend what that something was).

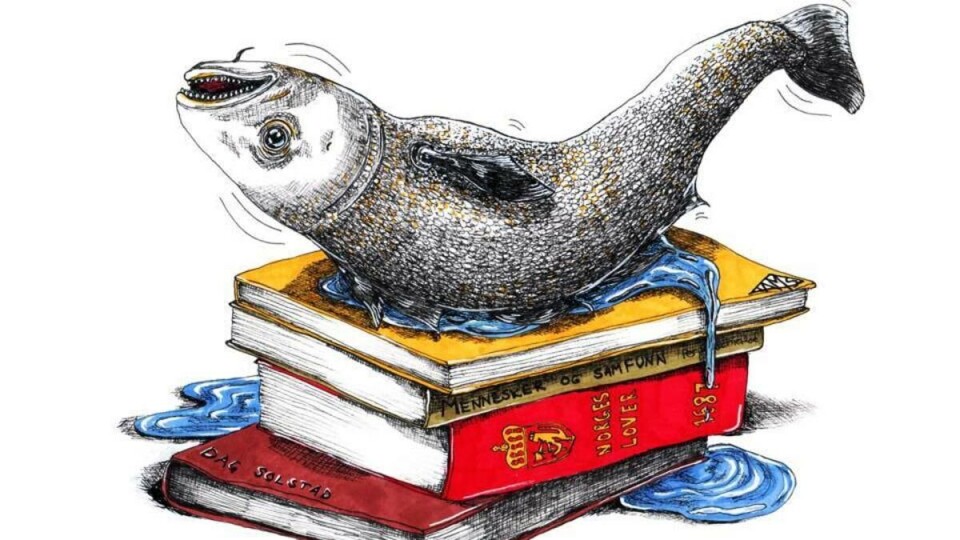

Until I set foot on the University of Oslo campus, higher education had been an alien concept. I had little to no ambitions. But individualism sank its teeth into me, and I left with the idea (probably absorbed from bad American movies) that I could be anything, if I just wanted it bad enough.

Fake it till you make it,» I thought.

Several months earlier, before the fateful sociology class, I had stood face to face for the first time with the intimidating Social Sciences building. Malnourished when it came to knowledge, I was almost manic, ready for the idealized student experience. I walked around in a haze of narcissistic dreams about becoming the female equivalent of Thomas Hylland Eriksen.

It didn’t take long before I saw that wasn’t going to happen. My Bourdieusian habitus, belief in my cognitive abilities, and intuitive sense of what could be accomplished became more and more fragile against the tidal wave of academic discourse I couldn’t understand.

I began to see I was missing basic knowledge, while other students could babble about it with no effort at all. I had to educate myself about the most elementary subjects. How does an election really work in Norway? What is parliamentarianism? Democracy? I wandered around campus like a sponge, reading, observing, listening, figuring out how to talk and act. «Fake it till you make it,» I thought.

But I started to fall behind. Clawing back what I had lost out on meant twice as much reading. It exhausted me. At the same time, I was in a state of constant anxiety, terrified I would be exposed and seen as stupid. I waited for the moment when, surrounded by enemies, I would be asked what I thought about the consequences of neoliberalism, the Oil Fund’s new investments, or deregulation of the economy.

Free education for all, no matter their background, is one way to equalize class differences. Meritocracy, the idea that everyone should have the same opportunities in education and the job market, regardless of class, gender, or ethnicity, has long been a political goal. It’s a nice thought, and I’m grateful that these basic Norwegian values allowed me to grab a piece of it. But there are limits to these ideals and attempts at enabling upward mobility. In principle we all have the same chances, but it’s up to us to forge our own fate.

Some people swim in academia, and others sink. Class background does not rule out an academic career, but the challenges are too often ignored. Some students get a leg up at home, while others don’t. We’re not the same, even though we’re on the same playground. The elephant in the room is that social differences are still there, even though more Norwegians are opting for higher education.

Statistics from SSB show that students with a resource-strong family background have the most success and go the farthest in academia. But it’s only gotten worse for students with parents who did not complete higher education. 60 percent of them now drop out after beginning higher education, versus 34 percent in 1992. The number of students who complete their education has stayed much the same.

The Norwegian social anthropologist Marianne Gullestad did fieldwork among Norwegians in the 1980s, and found that being similar to other people – not simply being equal, but resembling others – was a strongly rooted value. At the same time, she pointed out a central empirical finding: they liked to be similar, to the point of downplaying differences. They wanted everyone to be equal, even if it meant denying existing dissimilarities.

I’ve reconciled with myself that I’ll never be an academic superstar. I just don’t have the prerequisites for it. An op-ed by Synva Hjørnevik appeared in recently, where she wrote about the pressure on today’s youth. No one will tell us that in fact «only a few can be the best,» she wrote. We’re still the optimistic nineties generation who have grown up with the idea that we can all be the greatest.

If you found out you wouldn’t be able to complete your education in political science because of a lack of ability, would you apply in the first place? Yeah, right. No way. If we didn’t subscribe to meritocratic values, fewer people would take their chances. Class is still an issue in Norway.