When Oslo Was Kristiania:

Guided Tour of Norwegian Classic Hunger

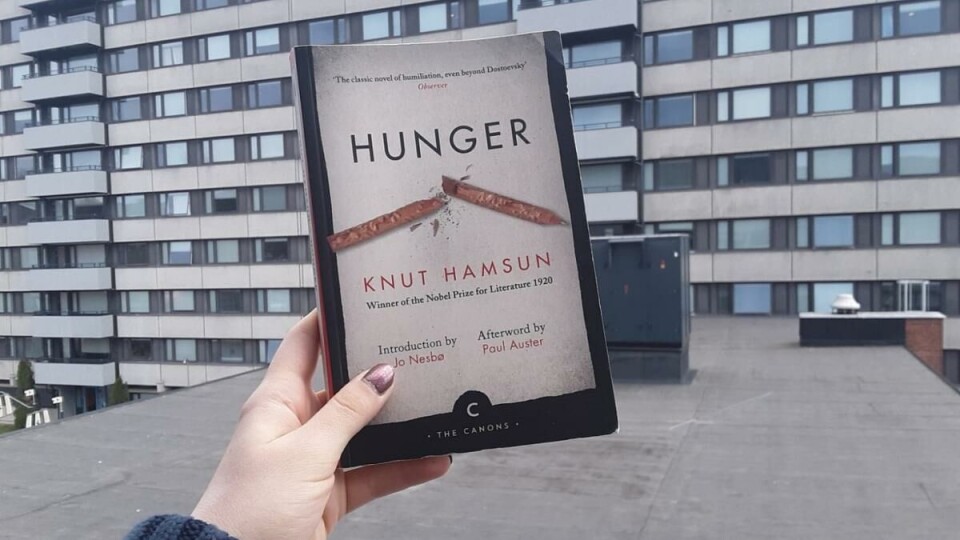

You get a unique chance to see Oslo through the prism of Norwegian classic literature - Knut Hamsun`s masterpiece Hunger.

The opening lines of Hamsun’s classic novel Hunger are some of the most famous in the Norwegian language: “It was in those days when I wandered about hungry in Kristiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set his mark upon him…” As with the nameless and penniless ambler, whose perspective structures the story, Oslo is bound to imprint itself on the international students who call the city their temporary home.

Historical Background

Though Oslo (formerly Kristiania under Norway’s unbalanced union with Denmark) has many enjoyable amenities to offer, it’s important to remember that Norway’s capital was not always the pinnacle of prosperity that citizens and sightseers alike experience today. Hunger or Sult in Norwegian was published in 1890, following an economic depression that characterized the previous decade, according to an entry in Den store norske leksikon. Though it is worth keeping in mind that Norway was fairly well-off in comparison with the rest of Europe at the turn of the 20th century, there is still a wide chasm between our modern understanding of a well-cared-for society, and that of a hundred years ago.

The Psychology of Poverty

In this historical context we meet the desperate protagonist of the novel, who begins the narrative nearly stripped of all his worldly possessions and already half-starved to insanity. The story is told in a stream-of-consciousness format, with the narrator oscillating wildly between generosity and hostility towards his fellow man as he navigates the city streets and the strained economic transactions that accompany poverty.

Because of how tightly the text is bound to the perspective of this suffering person, to read it is an intensely visceral experience. The protagonist has no name; he is dissociated from his personal identity and becomes a literal embodiment of the novel’s title: hunger. As I read the book, both the first and second time, I became painfully aware of my own body’s relationship to food and couldn’t help but imagine what it would feel like to go without: to feel my hair thinning, my teeth loosening, my mind slipping away. Because of my physical reaction to Hamsun’s (translated) words, it took me a few tries to actually get into the meat of the novel. However, once I began properly, I couldn’t put it down. I demolished the 200-ish pages in less than a day.

Like the perspective character of the novel, many of us struggle to connect with others during this time, and have to fight, sometimes to very little success, to be seen by the system.

Self-inflicted Hunger?

One question that the premise of the novel inevitably asks, but Hamsun refuses to definitively answer, is why this man is starving to begin with. When we meet the protagonist, his behavior is already erratic and paranoid, leaving the reader in doubt of his reliability as he explains the downward spiral, which has led him to this point. He’s the typical starving artist, occasionally getting a lucky 5 kr for a piece in the newspaper, which leads the reader to assume that his physical hunger is the product of an unwillingness to take on other kinds of work.

However, Hamsun takes care to mention in the first few pages of the novel that his perspective character has tried and failed to apply for other jobs, with his already destitute appearance locking him out of the labor market. But can we trust our narrator when he tells us these seeming “facts”? At the midway point of the novel, he passes up an opportunity to work on a ship, which (spoiler alert) turns out to be his saving grace at the end of the book. No extenuating circumstances or stage business prevent him from grasping this chance at once – a hundred pages of suffering could have been avoided if he had simply chosen to get on board sooner!

Because of the intense psychological preoccupations of the novel, the inherent questions about how the responsibility of the individual and the obligations of social systems ought to be defined go unanswered in a way that is both frustrating and thought-provoking.

Sailing Away from the City

As stated above, Hunger concludes with the protagonist sailing away from Kristiania after finally finding work on a ship. As he bids farewell to the city, he is “wet with fever and fatigue”, and the reader is called on to remember the opening line of the novel, which promised that Kristiania is a city “no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him”. Clearly, as we live vicariously through the half-destroyed body of the protagonist, we feel a mark has been left on us as well.

[Previously](uu), I’ve written about what it feels like to go home after studying abroad, and the lasting or fleeting impressions the experience might make on us. Likewise, Hunger is also a place worth reflecting on our relationship to the city that serves as our home for this semester.

Though I sincerely doubt and fervently hope that no international student reading this has undergone traumas while in Oslo like those Hamsun depicts, living in a foreign country can indeed come with its own psychological and economic hardships. Like the perspective character of the novel, many of us struggle to connect with others during this time, and have to fight, sometimes to very little success, to be seen by the system.

Seeing the Streets of Sult

Much of the protagonist's time is spent walking, writing and thinking amongst the streets of what is now called Oslo. Perhaps much of your time is spent this way as well, but hopefully in a better state of mind and with a bit of money in your pocket. If you want to familiarize yourself with the different routes and landmarks frequented by the perspective character of the novel, below you’ll find a guide to a selection of the places he mentions. Many of them you’re probably already familiar with, but as you encounter them again, they’ll take on the additional context of Hamsun’s story.

The Bazaars

This is the first named location in the novel. Though the translator calls this structure “the Arcades”, the Oslo Bazaars yields faster and more accurate Google search results. Reading the name, you might think that this is a place you’ve never heard of, but it’s more likely you’ve passed by it a few dozen times without knowing its name.

The Bazaars are housed in a brick, Romanesque-style building, which was erected in the mid-nineteenth century, about thirty years before the nameless wanderer of Hunger walks past them at the beginning of the novel. The Bazaars are now home to various shops and restaurants, but during the period, in which the novel is set, the arcades were used primarily as stalls for butchers to sell their wares. Using this building to imagine ourselves back into this era lends a different color – and smell! – to the city.

Palace Park

This is another location you’ve certainly heard of, and most likely visited yourself. If you haven’t, Spring is the perfect opportunity to bring a book and a thermos of coffee to this pleasant park and enjoy the warming weather. In Hunger, Palace Park is often named as the place where the protagonist does most of his writing, both his (very few) successful pieces, and his more bizarre attempts. Now, you can read Hamsun’s masterpiece in one of its most notable settings.

Queen’s Pavilion

The Queen’s Pavilion, or Dronningparken, is a section of Palace Park, which is generally only open from May 18 through October 1. The rest of the year, the Royal family uses the park while they spend time in Oslo. Though you’ll have to wait until after the 17th of May celebrations, in a few weeks you’ll be able to enjoy the spring flower beds and romantic tree-lined pathways.

St. Olavs plass 2

This address is the home of the character Ylajali, a woman with whom the protagonist of the novel enters a brief relationship. The only problem is that the reader cannot be sure she even exists. She seems to appear out of thin air, and the narrator’s thoughts and behavior are so erratic at this point it feels impossible to believe him when he tells us about this mysterious woman.

Though Ylajali exists only in fiction, her home is still very much real, and the building is now home to Cafe Tekehtopa, a restaurant and bar decorated in a 19th-century style. Though it opened in the late 1990’s, it was converted from a pharmacy, which opened in 1892, two years after the publication of Hunger. The restaurant also maintains a small museum dedicated to preserving this part of the building’s history.

Parting Words

I believe that moving physically within our version of the world that Hamsun evokes in his prose is a valuable experience – an experience that can be as visceral as the novel itself, and one that demonstrates strands of continuity between the present and the past.

All that remains for me to say is a final encouragement to read the book, that strange book that no one reads without it leaving its mark on him.